He heard a sobbing coming from the back of the cellar and found the old monk leaning over one of the original books, crying. Hours later, nobody had seen him, so one of the monks went downstairs to look for him. The head monk said, ‘We have been copying from the copies for centuries, but you make a good point, my son.’ The head monk went down into the cellar with one of the copies to check it against the original.

He pointed out that if there were an error in the first copy, that error would be continued in all of the other copies. The new monk went to the head monk to ask him about this. He noticed, however, that they were copying copies, not the original books. He was assigned to help the other monks in copying the old texts by hand. Wallace opened with to illustrate the importance of textual criticism,Ī new monk arrived at the monastery. Wallace says there are many scribal alterations (#1), but very few that are meaningful (#3) and viable (#2) in fact, Wallace points out that, “No essential Christian belief is affected by any viable variant… No, not one.” 1 In this video, “ Is What We Have Now What They Had Then?” Wallace discusses three key questions for textual critics,ġ) Quantity: How many scribal alterations are there (deviations from text in spellings, additions-even if they’re of no consequence)?Ģ) Quality: What kinds of textual variants are there?ģ) Orthodoxy: What theological beliefs rest on theologically suspect passages?

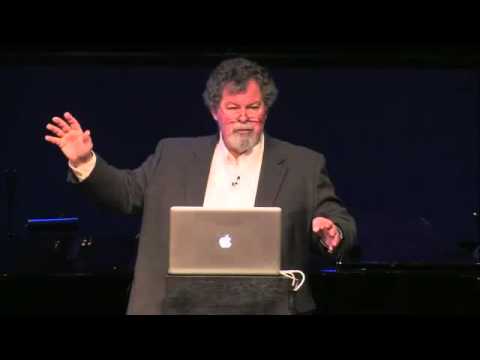

To help answer these objections I am posting the following video by Daniel Wallace, Professor of New Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary, and the Executive Director of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts ( CSNTM). In many respects, this is a red herring because Muslims who believe the Quran need to prove that a book from heaven ( Injeel) was given to Jesus who then gave it to his followers (cf. Muslims argue against the reliability of the New Testament by pointing out that there are variants in the different manuscripts.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)